South Korea’s economy is deteriorating, squeezed by political instability and a weakening currency.

The won has lost over 12% of its value against the dollar in 2024, making it Asia’s worst-performing currency.

This sharp decline has driven up import costs, fueled inflation, and left policymakers balancing the need for economic stimulus with concerns about financial stability.

The South Korean political crisis: what happened?

In December 2024, President Yoon Suk-yeol attempted to impose martial law—a move that quickly backfired.

The controversial action led to his impeachment and subsequent arrest. This was the second presidential impeachment in South Korea since 2016 and the first-ever arrest of a sitting president.

The fallout has triggered the country’s largest political crisis in decades, disrupting governance and delaying critical economic decisions.

The crisis has left South Korea without clear leadership at a time when the global economy is fraught with uncertainty.

Acting President Choi Sang-mok, who is also the finance minister, is attempting to stabilize the situation, but the government’s reduced capacity to implement policies has become a major concern.

What’s happening with the South Korean won?

The South Korean won fell to its lowest level in 15 years in December 2024, trading at 1,487 won per US dollar.

This represents a dramatic 5.3% drop in December alone, the second largest monthly drop in history, only behind the Russian ruble’s decline in February 2022.

According to the Bank of Korea (BOK), political instability weakened the currency by approximately 30 won against the dollar.

The arrest of Yoon temporarily stabilized the exchange rate, but sustained recovery will depend on how quickly political stability is restored.

A weak won has serious consequences for South Korea’s trade-reliant economy.

Import prices for essentials like gasoline and sugar have surged by up to 97%, adding inflationary pressure.

December’s consumer price index rose 1.9% year-on-year, up from 1.5% in November.

The BOK estimates that the currency depreciation alone contributed 0.05 to 0.1 percentage points to this increase.

Risks of ‘stagflation’?

South Korea’s recent stagnation in growth and rise in inflation have started raising some questions about whether the nation’s economy could face a rare scenario of “stagflation”.

The government recently revised its 2025 GDP growth forecast down from 2.2% to 1.8%, reflecting the worsening outlook.

Domestic demand is weakening, and export growth is slowing, indicating a shift to a prolonged low-growth trajectory.

Analysts warn that prolonged political instability could further dampen growth while inflationary pressures from the weakened won add another layer of strain.

External factors exacerbate the risk.

The return of Donald Trump to the US presidency raises concerns over potential protectionist trade policies, including tariffs on exports from major economies like South Korea.

Such measures could disrupt global supply chains and further suppress export demand, deepening South Korea’s economic stagnation.

Interest rates: to cut or not to cut?

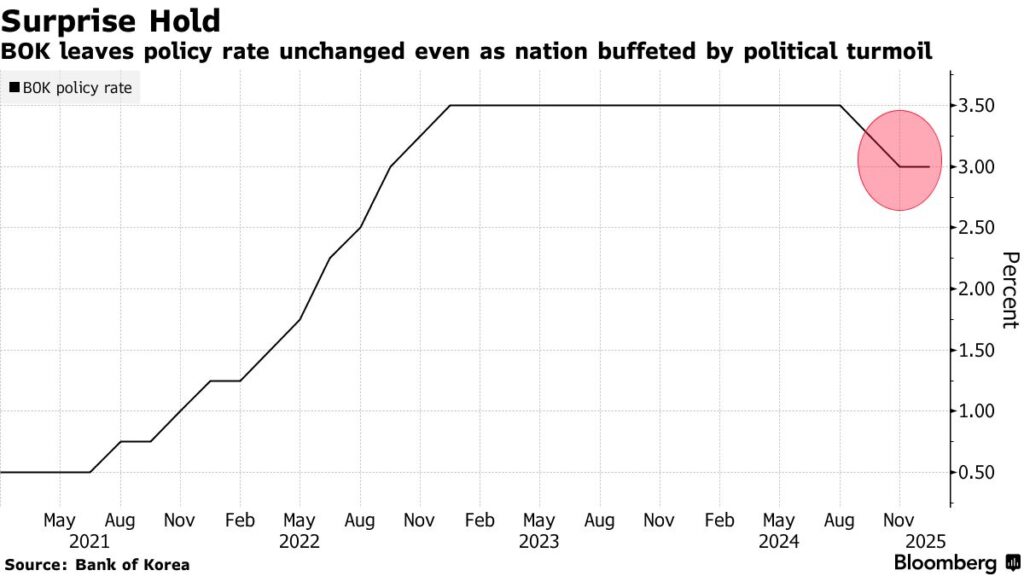

The Bank of Korea has been hesitant to reduce its key interest rate, holding its policy rate at 3% in its most recent meeting in January 2025.

This was seen as a surprise move after two consecutive reductions in October and November.

Governor Rhee Chang-yong explained that the decision was influenced by the need to stabilize the won, which remains under significant pressure.

Further rate cuts could weaken the currency further, exacerbating inflation and financial instability.

However, the BOK has expressed its openness to additional rate cuts in the near term, with economists predicting that the policy rate could fall to 2.25% by the end of 2025.

Rhee emphasized that resolving political instability is a more critical priority than immediate monetary easing.

“A normalization of the political process is way more important than lowering interest rates a month earlier or later,” he said.

Some economists remained worried that holding rates too high could stifle economic recovery in the long run.

External pressures and future risks on South Korean economy

South Korea’s economic challenges are not confined to domestic issues.

It also faces risks from other nations, with potential US trade policies under Donald Trump likely to create headwinds.

Tariffs on Chinese goods could disrupt supply chains and dampen demand for South Korean exports.

Conversely, such policies could offer opportunities if they improve the competitiveness of South Korean goods in the US market.

The BOK and economists also point to structural growth risks. South Korea’s potential GDP growth is expected to average 2% from 2023 to 2026, declining to 1.9% by 2030.

This signals a shift to a low-growth trajectory unless significant reforms are implemented.

Acting President Choi has announced several initiatives to support the economy, including front-loading fiscal spending and expanding aid programs for small businesses.

The BOK has increased its support for smaller companies, raising the budget for these programs from 9 trillion won to 14 trillion won.

What lies ahead for South Korea?

South Korea’s economic recovery hinges on political stability.

Without it, investor confidence will remain shaky, and the currency could face further depreciation.

The longer the crisis drags on, the greater the risk of long-term damage to the country’s economic foundations.

While the government and the central bank are taking steps to mitigate immediate risks, broader structural reforms are needed to address underlying vulnerabilities.

These include reducing dependence on exports, diversifying the economy, and strengthening social safety nets to ensure resilience in the face of future crises.

The road to recovery will not be easy, but resolving political turmoil is the first step toward restoring confidence and rebuilding momentum for Asia’s fourth-largest economy.

The post Political instability and a falling won: what lies ahead for South Korea’s economy? appeared first on Invezz