There is a different kind of discussion going on ahead of the Federal Reserve’s interest rate decision on Wednesday.

Usually, investors are concerned with the “if” and “how much” are interest rates going to change.

But this time, everybody is wondering whether the central bank actually has enough data at its disposal to make the best decision.

For a central bank that prides itself on being data-driven, a situation where data remains frozen by a month-long US government shutdown is far from ideal.

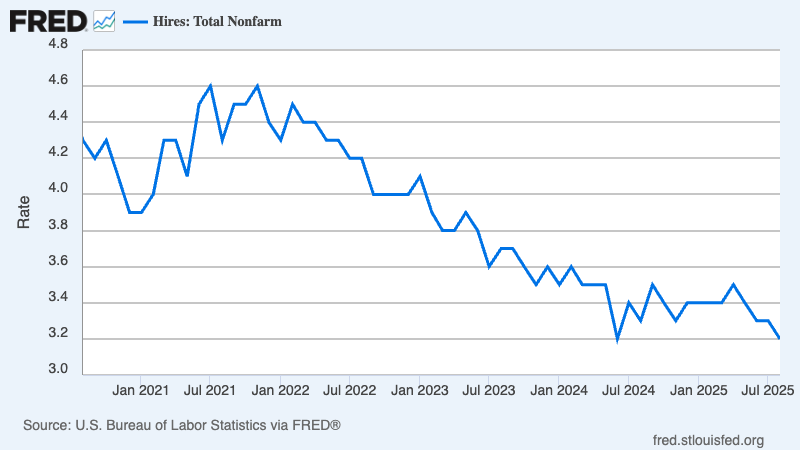

Inflation is rising again, hiring is slowing, and consumer confidence has fallen to its lowest point in half a year.

And the official numbers that usually tell policymakers how serious those trends are simply do not exist.

This is not just another routine rate meeting.

It is the first time in modern US history that the world’s most data-dependent central bank is setting policy largely on instinct.

How the numbers went dark

Since October 1, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Bureau of Economic Analysis, and the Census Bureau have all stopped publishing their usual monthly updates.

The September jobs report was never released and October’s will never be collected.

The Commerce Department’s GDP estimate is also on hold, and it was due this week.

Only the September consumer price index made it out before the lights went off, showing annual inflation at roughly 2.8%, still higher than the Fed’s 2% target.

That figure alone leaves the Fed in a bind. It suggests prices are rising too quickly, just as hiring weakens and layoffs spread from logistics and retail into technology and manufacturing.

Without these official figures, the data infrastructure that anchors the Fed’s judgment has collapsed.

Private economists and asset managers are filling the gap with “alternative data” drawn from credit card spending, online job listings, and supply-chain indicators.

Powell has admitted that these sources are useful as background but cannot replace official statistics. “They work better as a supplement than as a main course,” he said earlier this month.

What the Fed can still see

Inside the Fed, policymakers are working from a patchwork of evidence.

The latest central bank’s Beige Book, which was released on October 15, reported that household spending has cooled and that manufacturing is suffering under higher tariffs.

The Conference Board’s consumer confidence index has fallen to its lowest level since April.

Major employers, including UPS, Amazon, and Nestlé have announced tens of thousands of job cuts.

Private payroll data suggest hiring is slowing, though unemployment remains near 4%.

Second-quarter GDP growth was 3.8%, but economists doubt that pace has continued.

The AI industry and high-income consumers are still spending freely, while lower-income households are cutting back.

Credit card delinquencies and auto-loan defaults are creeping higher.

What the Fed chair is seeing is a fragmented economy where strength in a few sectors masks stagnation elsewhere.

Without the normal stream of official data, the Fed cannot know whether the slowdown is temporary or the start of something deeper.

Pressure from the White House

The uncertainty has made the Fed’s independence harder to defend.

President Trump has spent months urging large and immediate rate cuts, arguing they would lower the cost of government debt and spur growth before next year’s election.

He has called for cuts totaling three percentage points, which is twelve times larger than what markets expect today.

The pressure has moved beyond rhetoric.

Trump tried to remove board member Lisa Cook, the first such attempt in the Fed’s 112-year history, and replaced another governor with a loyalist who voted for a bigger cut in September.

A federal judge later blocked Cook’s dismissal, but the message still passed.

The White House is ready to test the limits of central-bank independence.

The campaign has also spilled into the succession race. Powell’s term ends next year, and five candidates seen as sympathetic to Trump’s policy views are vying to replace him.

Two of them sit on the Federal Open Market Committee and will vote today.

What do expect from the Fed’s interest rate decision

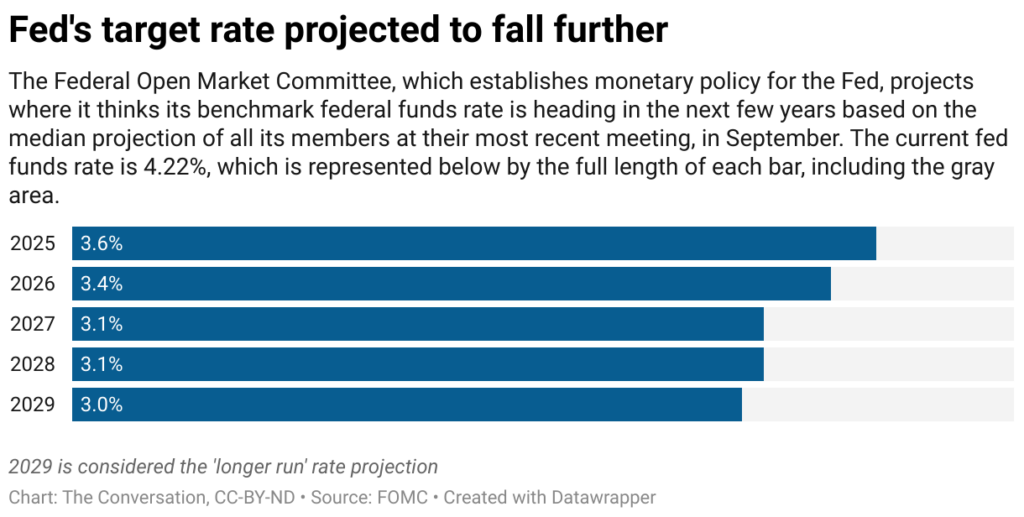

Markets have priced in a quarter-point reduction to a range of 3.5-3.75%. A smaller move would signal defiance of the White House. A larger one would look like surrender.

Powell is expected to frame the decision as a cautious adjustment in a foggy environment, reiterating that the Fed’s goals remain stable prices and full employment even when the data are unstable.

Investors will listen for any hint on the balance sheet, where “quantitative tightening” is still draining liquidity from markets.

As Joshua Mahony, chief market analyst at Scope Markets, notes, “The lack of data available to the Fed means that the so-called data-dependent approach comes into question if the blackout continues. With liquidity stresses arising, attention will turn to whether they end quantitative tightening or push that to the end of the year.”

The rate cut itself may not move markets much, but what Powell says about liquidity, confidence, and policy visibility will.

The Fed’s challenge is no longer about the precise level of borrowing costs.

It is about proving that an institution built on measurement can still function when the measurements disappear.

The most telling risk for Powell is not higher inflation or slower growth. It is that the public, investors and politicians start to believe the Fed no longer has a clear view of the economy at all.

Once that belief takes hold, interest rates ultimately lose their meaning, and the world’s most powerful central bank becomes just another player guessing in the dark.

The post Interest rate decision preview: What to expect from a blindfolded Fed appeared first on Invezz