The global AI boom looks unstoppable when measured by stock prices. Trillions of dollars in market value rest on the idea that machines are changing work, productivity, and profits.

But AI is not just a technology race. It is becoming one of the largest debt-funded infrastructure projects in modern history, and the strain is starting to show.

In the past year alone, the flow of money into AI data centres has changed the structure of credit markets, pulled private lenders into the centre of tech finance, and tied the fate of many firms together in ways few investors can clearly see.

Looking at the same thing, some call it growth, others call it leverage.

AI stops looking like software

For most of the past two decades, big technology firms followed a familiar pattern. They invested heavily in research, built software platforms, and scaled at low marginal cost.

Cash piles grew faster than borrowing. But not anymore.

Training and running advanced AI systems require vast physical infrastructure. Data centres must be built quickly. Power contracts must be secured. Chips must be purchased in enormous volumes.

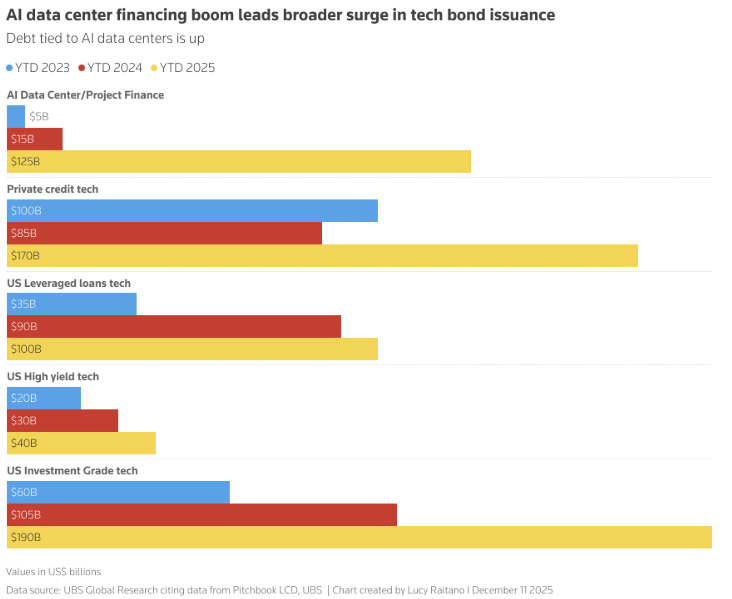

According to UBS, AI data centre and project finance issuance reached about $125 billion in 2025, up from just $15 billion a year earlier.

McKinsey recently estimated that total data centre spending could approach $7 trillion by the end of the decade.

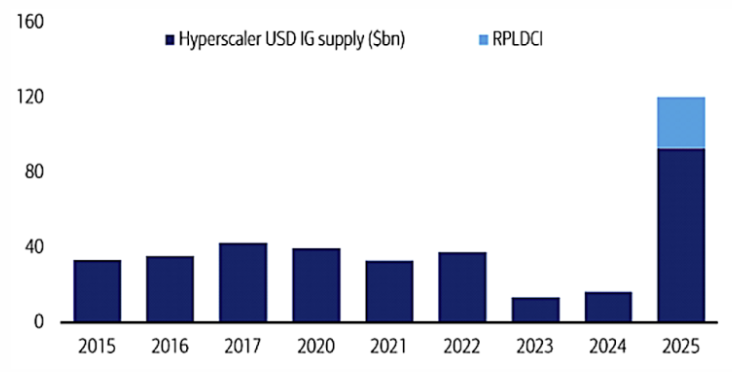

Even the largest firms cannot fund this alone. Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft and Oracle issued roughly $121 billion of new debt this year, more than four times their recent annual average, according to Bank of America.

At least another $100 billion is expected next year. These companies still generate strong cash flow, but the pace of spending has outgrown their ability to self-fund without changing how they operate.

The result is a sector that now looks less like software and more like utilities or telecoms. Returns depend on utilisation, timing, and financing costs.

That is a different risk profile, and credit markets are beginning to price it.

Oracle shows how fast sentiment can turn

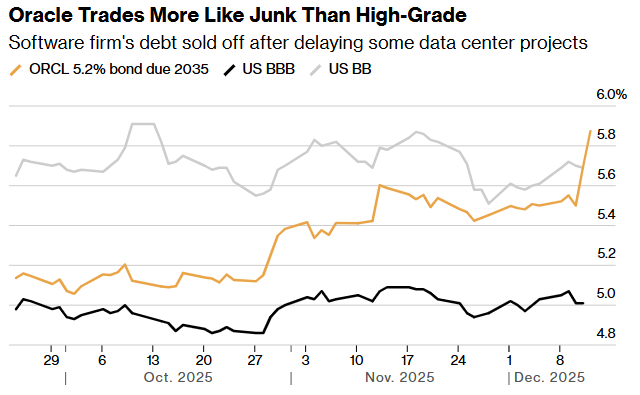

Oracle has become the clearest test case for this new AI economy. The company surged earlier this year on optimism around cloud growth and its deep ties to OpenAI.

At its peak in September, Oracle shares had nearly doubled for the year. Since then, the story has changed.

After missing revenue expectations, Oracle shares fell more than 11% in a single day. Larry Ellison’s net worth dropped by about $25 billion.

More important than the stock move was what happened in credit markets.

Oracle’s investment-grade bonds, including $18 billion issued in September, have sold off sharply. Paper losses now exceed $1 billion. Credit default swap spreads have risen to levels last seen during the financial crisis.

The web of circular financing

Oracle’s stress sits within a much wider network of financial links. At the centre of that network are Nvidia and OpenAI.

Nvidia is the clear winner so far. It sells the chips every AI system needs and posts strong profits.

But even Nvidia’s success depends on others continuing to spend. Many AI developers do not have the cash to buy chips outright.

To solve that, Nvidia has invested equity in customers, extended financing, and backed deals that help fund data centres. The cash often flows out and then back again as chip purchases.

OpenAI plays a similar central role. It is a major customer of Oracle, Amazon, Microsoft, and CoreWeave. It is also an investor in some of them.

OpenAI has committed to buying hundreds of billions of dollars of computing power over time while generating about ten billion dollars in annual revenue and large losses. Its profitability is still years away.

Another prime example is CoreWeave, which currently has no profits, about $14 billion in debt, and tens of billions more in lease obligations. Around 70% of its revenue comes from Microsoft.

Nvidia is both a supplier and investor, while OpenAI is both a customer and a partner.

Money circulates inside a small group of firms, amplifying growth when conditions are good and risk when they are not.

This structure allows the system to expand faster than traditional balance sheets would permit. It also makes it harder to see where losses would land if demand slows or timelines slip.

When debt goes off the books

As borrowing rises, companies have looked for ways to keep balance sheets clean. Special-purpose vehicles have become common.

Meta, xAI, Google, and others have used these structures to finance data centres and chip purchases without recording the full debt load.

The vehicle borrows, builds, and leases the asset back to the tech firm. These arrangements preserve credit ratings and flexibility.

They also reduce transparency. Rating agencies and investors see less risk at the corporate level, even though the economic exposure remains.

Similar structures were widely used before 2008, both in banking and at companies like Enron.

Private credit has stepped in to fund much of this growth. Morgan Stanley estimates private lenders could provide more than half of the $1.5 trillion needed for data centres through 2028.

These lenders are lightly regulated. Disclosure is limited. Links to banks and insurers are growing, but they are hard to map in real time.

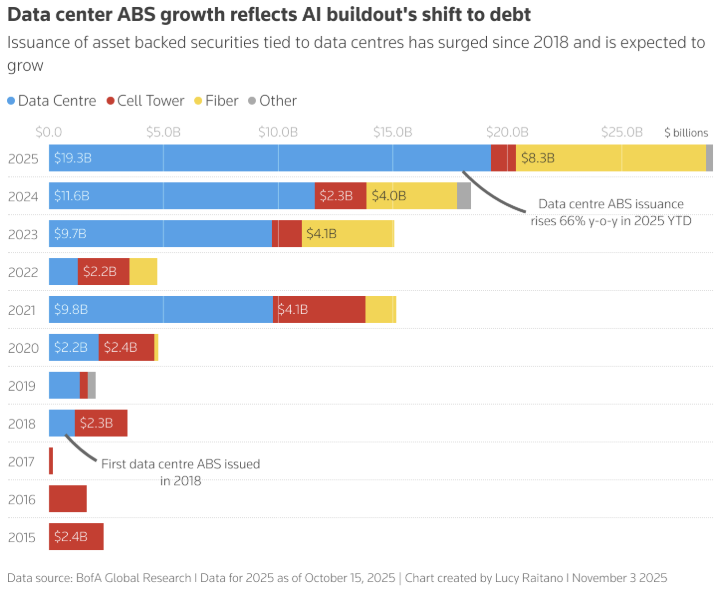

Securitisation adds another layer. Data centre cash flows are being bundled into asset-backed securities.

Digital infrastructure now accounts for about $82 billion of the US ABS market, up ninefold in under five years, according to Bank of America.

More supply is expected next year. Investors buy rated products without always understanding the assets inside.

Some loans are backed by GPUs themselves. As newer chip models arrive, older ones lose value.

If collateral prices fall, lenders may demand repayment or sell chips into a weak market, pushing prices down further.

Markets are still absorbing the supply. Spreads have widened. Stocks are volatile.

The AI economy is now bound together by leverage, timing assumptions, and complex financing.

The post Yes, the AI boom has a balance sheet problem appeared first on Invezz