Wars like the Russia-Ukraine one don’t end when diplomats sit down. They end when pressure becomes harder to absorb than compromise.

4 years later, Russia and Ukraine are still fighting, still talking, and still testing how much strain their systems can take before something gives.

The battlefield has frozen into lines, but the conflict itself has not. It has moved into energy grids, balance sheets, labour markets, and reserve accounts.

A war defined by attrition rather than movement

The military situation has settled into a grinding stalemate.

Russian forces have not achieved decisive breakthroughs, despite sustaining one of the highest casualty rates seen by any major power since the Second World War.

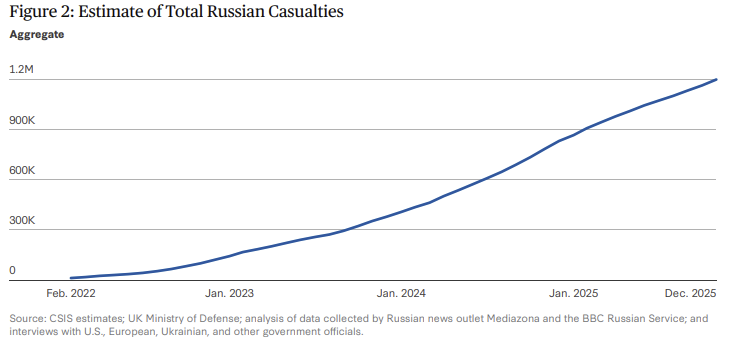

A recent study estimates Russian casualties at roughly 1.2 million, with as many as 325,000 killed.

Ukraine’s losses are smaller but still devastating, with independent estimates suggesting 100,000 to 140,000 dead and total casualties near 600,000.

At the moment, neither side has the capacity to rapidly escalate without severe consequences.

Ukraine faces manpower limitations and growing difficulties in rotating troops.

Russia has leaned heavily on mobilisation, regional recruitment, and financial incentives, which keep numbers flowing but drain labour from civilian industries.

The war continues not because either side is winning, but because both still believe the other will break first.

That belief is now being tested outside the battlefield.

Winter warfare and civilian pressure as a strategy

Russia has returned to a familiar tactic. Instead of pushing forward on land, it has intensified attacks on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure during one of the coldest winters in years.

Temperatures in Kyiv and other cities have dropped below minus 20 degrees Celsius, while repeated drone and missile strikes have caused long blackouts and heating failures.

This winter feels different from the previous ones. Backup generators and batteries that once bridged short outages are now being exhausted by longer disruptions.

Emergency warming centres have become essential, not symbolic. European officials describe the campaign as deliberate pressure on civilians, not incidental damage.

However, the effect has not been capitulation. Surveys and local reporting show fatigue, anger, and fear, but also a strong resistance to territorial concessions.

The attacks appear to have narrowed Ukraine’s political room for compromise rather than widened it, especially while strikes continue during negotiations.

Peace talks that move but do not narrow the gap

Talks brokered by the United States in Abu Dhabi have resumed with senior delegations from Washington, Kyiv, and Moscow.

Publicly, all sides signal willingness to engage. Privately, however, expectations remain low.

The central issue remains land. Russia continues to demand that Ukraine cede the entire Donbas region, including areas still under Ukrainian control.

Kyiv has rejected that position, although it has indicated it could consider demilitarised zones or adjusted military deployments.

Those signals stop well short of formal territorial surrender.

Other disagreements are just as deep. Moscow rejects the presence of European troops on Ukrainian soil.

Ukraine insists that external forces are necessary for any credible security guarantees.

Russia also wants limits on the size of Ukraine’s armed forces, a condition Kyiv sees as incompatible with survival.

The continuation of Russian strikes on Kyiv during talks has undermined confidence further.

Diplomacy exists, but it is operating in parallel with escalation, not replacing it.

Russia’s oil trade still flows, but on weaker terms

Russia’s economic strain is becoming easier to measure.

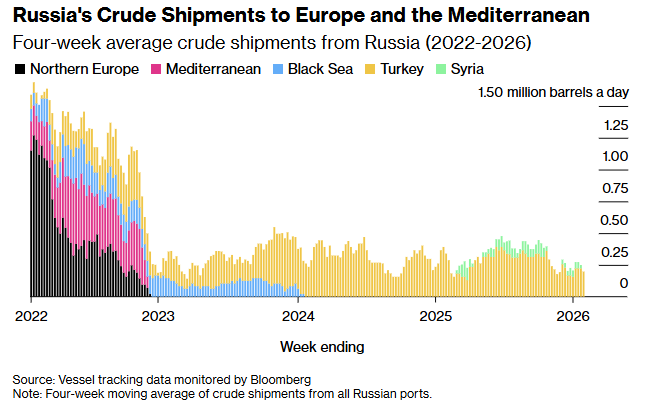

Oil exports remain surprisingly resilient in volume, as seaborne shipments averaged about 3.27 million barrels per day in the four weeks to early February, according to Bloomberg vessel tracking.

China has resumed its position as Russia’s largest buyer, taking roughly 1.65 million barrels per day by sea, plus another 800,000 by pipeline.

India, however, has started to pull back. Imports fell to around 1.12 million barrels per day in January, the lowest level since late 2022.

What makes this significant is that India had become Russia’s most important swing buyer after Europe cut imports. Fewer buyers mean less pricing power.

The stress shows up in logistics. More than 140 million barrels of Russian crude are now sitting on tankers at sea.

Ships delay declaring destinations, wait weeks to unload, or change course mid-voyage. Oil is moving, but slowly and at a discount.

Russian crude continues to trade more than 20% below international benchmarks.

Prices rose modestly in recent weeks, lifting weekly export revenues to just under $1 billion.

That provides short-term relief, although it does not change the underlying problem.

Russian oil prices remain below the fiscal level required to sustainably replenish state reserves.

Budget pressure and a shrinking safety cushion

The most serious warning signs appear in Russia’s public finances.

Official targets assume a budget deficit near 1.6% of GDP, while internal estimates suggest something closer to 3.5-4.4% if current conditions persist.

Energy revenues are projected to undershoot plans by roughly 18 percent, while spending continues to rise due to military needs and social payouts.

January data was stark, with oil and gas revenues falling to their lowest level since mid 2020.

At the same time, a strong rouble has reduced the value of export taxes, since oil is sold in dollars but taxed in local currency.

Russia still has about 4.1 trillion roubles in liquid fiscal reserves. At the current pace of withdrawals, analysts estimate most of that buffer could be gone within a year.

Large banks in Russia now expect between two and three trillion roubles to be drawn down in 2026 alone.

Financing the deficit is possible, but expensive, as interest rates remain near 16%.

That limits the state’s room to borrow without crowding out private activity or deepening stagnation.

With a 12-month runway and high borrowing costs, Russia’s leverage in negotiations is getting increasingly thin.

A war economy built on confidence rather than growth

What keeps the system running is not growth, but circulation. The state pays large bonuses to soldiers and compensation to families.

Banks absorb the cash by offering deposit rates above 20%. Those deposits are then recycled back into government debt.

The state regains liquidity and repeats the process.

It works as long as households trust banks and believe withdrawals will remain unrestricted.

The system becomes fragile when confidence wavers. Rumours, restrictions, or visible stress can push people to pull cash at once.

That is when emergency controls tend to appear, which stabilise numbers but damage trust further.

There is also a social dimension. War payments have lifted incomes in remote regions that had long been neglected.

Expectations have risen. If those flows slow while living costs stay high, frustration will grow far from Moscow’s insulated core.

This is where economics and diplomacy intersect. Russia can continue fighting, but the cost of doing so is rising faster than its room for error.

The war no longer depends only on weapons or manpower. It depends on whether the financial loop holds together long enough to force concessions at the table.

The post Why Russia’s economy is becoming a constraint in Ukraine peace talks appeared first on Invezz