Things used to be simple in the markets. AI would carry US stocks higher for a couple of years, regardless of what the economy looked like.

But this story broke down in recent days, even with the king of AI stocks, Nvidia, delivering another strong set of numbers. The market cheered for an hour, and then everything reversed.

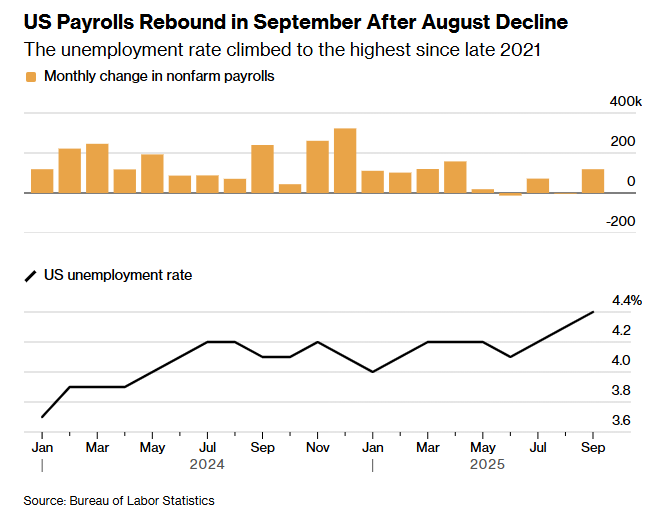

At the same time, the delayed US jobs report finally arrived. It showed a labor market that is still adding jobs but also losing momentum. Rate cut hopes faded a little more.

Putting together these moves has rattled investors. And now everybody is confused. Is the market selloff about stretched AI valuations, a softer US labor market, or a Federal Reserve that is in no hurry to cut? Plus, a gap in the data leaves everyone guessing.

What the latest jobs report really showed

The latest Employment Situation report covers September and only came out in late November because of the government shutdown.

It showed nonfarm payrolls up by 119,000 for the month, compared with a consensus forecast of around 51,000 and after a decline in August.

The unemployment rate rose again to 4.4%, the highest level since late 2021.

Things don’t look bad on the surface. Jobs are still growing, and the unemployment rate is far from crisis territory.

The details are less comfortable. Job gains were narrow. Health care and leisure, and hospitality did most of the hiring.

Manufacturing, transportation and warehousing and parts of business services shed workers.

Wage growth eased as well. Average hourly earnings rose 0.2% on the month and 3.8% over the year, still slightly above the current inflation rate.

That supports consumption for now, but does not point to booming demand.

At the same time, revisions told a weaker story. Earlier months were marked down, and August now shows a small net loss in payrolls.

Put simply, the trend in the US labor market is no longer one of steady tightening. It is one of slow hiring, more layoffs in some cyclical sectors, and a gradual rise in unemployment.

For the Federal Reserve, this is awkward rather than decisive. The report is old. It describes the state of the US labor market before the longest shutdown in US history and before the latest round of corporate layoff announcements.

It does not give a clear reason to cut rates again in December, and it does not scream recession either.

Why an AI darling could not save the market

Earlier this week, investors looked to Nvidia and the wider AI complex for a fresh boost.

Nvidia once again beat expectations on revenue and profit. For a brief window that seemed enough to send the S&P 500 higher and the Nasdaq 100 up more than 2%.

Then the mood turned. By the close, the S&P 500 had fallen around 1.6% and the Nasdaq 100 had swung from a strong gain to a loss of about 2.4%.

Nvidia itself ended down roughly 3% and the main US equity benchmark is now about 5% below its recent peak.

The numbers from Nvidia were not the issue. The concern is what those numbers represent.

AI leaders and data center suppliers are still posting strong growth. Yet the spending needed to support that growth is huge. Investors are increasingly asking whether the profits that arrive over the next five years will justify today’s market values.

One detail that bothered traders was Nvidia’s rising accounts receivable balance.

If demand is as strong as the top line suggests, then the lag in cash collection raises questions. Are customers stretching payments as they juggle their own capex budgets.

That adds to the feeling that AI demand might be more sensitive to the broader economy than many assumed.

US equity multiples remain close to levels seen in earlier periods of investor enthusiasm, even after the latest pullback. When valuations are high, good results are no longer enough.

Investors want proof that AI is a durable cash generator in an economy that is no longer booming.

The failure of a strong Nvidia quarter to push markets higher sent a clear signal. The AI trade no longer looks untouchable.

Hedging, crowding and the mechanics of a selloff

What turned a wobble in confidence into a sharp slump was not only fundamentals. It was how portfolios were positioned.

On the day of the reversal, the S&P 500 opened almost 2% higher before dropping into negative territory.

The VIX jumped above 26. It was the biggest intraday swing since market turmoil in April.

Goldman Sachs trading desks reported a rush to hedge risk and protect profit and loss.

Clients increased short positions in equity futures, exchange-traded funds, and custom baskets.

At the same time, liquidity thinned. The top of the order book in S&P futures showed less than half its usual depth. That makes every large order move prices more than usual.

The pattern is familiar. AI and mega-cap tech stocks had become crowded trades.

Many institutional portfolios relied on them for returns this year. When the narrative shifted even slightly, investors did not just trim positions. They moved to reduce exposure aggressively and bought downside protection.

Dealers on the other side of those trades then had to adjust their own hedges, which amplified the move.

The index also slipped below its 100-day moving average. That technical level matters for systematic strategies.

Once it broke, more selling followed. None of these mechanics says anything new about the US labour market or the true value of AI. They explain why prices fell so far so quickly once doubt appeared.

Interestingly, Goldman’s analysis of similar reversal days since the late 1950s shows that, on average, markets rose in the following days and weeks.

And although history does not guarantee a rebound now, it does suggest that episodes like this are often more about position adjustment than a lasting change in the economic outlook.

The role of missing data and the Fed

Behind the headlines there is another source of unease. The shutdown did not just delay reports. It created a hole in the data just as the Fed is weighing its next move.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics was unable to run the October household survey. That means there will be no official October unemployment rate or participation figures. Those numbers cannot be recreated after the fact.

October payrolls from the employer survey will eventually be released, but only as part of the November report.

That combined release is scheduled for 16 December. The Fed meets on 9 and 10 December.

Policy makers therefore have to make a decision on interest rates without a clean read on the labour market for two months.

Before the shutdown, markets had priced a high chance of another rate cut in December.

As growth slowed and inflation edged lower investors expected the Fed to keep easing.

After the September jobs report and the data gap created by the shutdown, those expectations have shifted.

Futures now point to a much smaller probability of a cut next month and more emphasis on early 2026.

That means that a labor market that is softening without being clearly weak gives the Fed room to wait. At the same time, the higher starting point for unemployment means there is less buffer if a negative shock hits.

Markets are reacting to that uncomfortable mix. Growth is slower. The policy safety net is further away than investors hoped in the summer.

A new type of risk in the data

There is one more angle that deserves attention. The quality of the jobs data itself is changing. The Bureau of Labor Statistics plans to update how it estimates employment in new and closing small firms from early 2026.

That so called “birth death model” has a large impact on monthly payroll figures, especially late in the cycle when small business dynamics can turn quickly.

The new method will rely more on current sample information each month.

If recent job creation has been overstated as the economy slowed, those changes and the usual annual benchmark revisions could make the past few years look weaker in hindsight.

That would affect how investors judge the strength of the US labour market during the AI boom.

A market that already questions AI valuations and the timing of rate cuts may have to digest a different picture of recent job growth as well.

The post What is really driving the market slump: AI bubble fears or a fragile labor market? appeared first on Invezz